MEGAN PLUNKETT RETURN TO SENDER

JANUARY 18 – FEBRUARY 29, 2020

Statement

Megan Plunkett, January 2020

Douglas Eklund, writing about the Pictures Generation, said of a geography that is very known to me: “...that relentlessly planar, ghosttown effect—the sense that you are perceiving only the hovering illusion of a missing original—is particular to Los Angeles.”

While I agree, I can also take this further.

I am interested in Eklund’s use of the phrase, “missing original.” Once during grad school, a visiting artist asked me what my “missing image” was. I didn’t have an answer then and still might not.

A couple years ago, I drove out to the desert, to a police station, in search of an image. I knew that this particular station had the county’s police archives, and that several members of my family had records there. I knew about the incidents in broad strokes and didn’t need to read the police reports—I just wanted to look at pictures. For several years I worked as an unlicensed private investigator in Los Angeles. Sometimes archival information related to cases had images included in the records, so I was rolling the dice and hoping that this would be the case here. The incidents (or, “crimes”, if we must) lent themselves to the cinematic, which I’ll leave at that. The clerk told me that no images were taken at any of the scenes related to the records I had inquired about. Perhaps this is my missing image, but it doesn’t mean that I can’t see it. What I see might not be right, but it’s what I have to live with.

Coming of age in media culture is a way of being seduced into consumerism and eased into a constant crisis of authority. This has been true and it remains so, and now also includes whatever roving public arraignment we have agreed upon as “reality,” itself an endlessly shifting target. I am aware that the uncanny often manifests in the everyday.

Photographs have historically lured us with the promise of an almost forensic objectivity, but they are also only a pause in time’s unfolding, an improvisation that necessarily produces an estrangement of realism. An image is a stop the mind takes in between uncertainties. I am interested in generating tension between the real and the really real (which is probably not even a “real” thing at all, again only a fragment of the imaged world, itself part of a myth that things are ever “whole” or “correct”). Recurring strategies include doubling and repetition, disruptions in our sense of presence and absence, and a lurking sense of humor. Everything is a double, and sometimes the double is me. “The mirror cracks, I am the other, I always was.”

Conventional reads of photography often rely on seeing images as identical to their subject matter, which is not unrelated to an understanding of images that banks on a kind of image-as-consumable-object logic. I am interested in how to see beyond this. This also extends to how I think about what we might call “genre” and the limits of that. My subjects are, most often, things that are obvious in some way, and have historically included: cars, dogs, UFOs, images of the American West. There are things that we are not only very used to seeing represented, but also which whole industries (both cottage and hyper-commercial) are built around. They are things that we are used to having a certain kind of transactional relationship with, subjects that lend themselves to an attempt at bucking “the creep of reification.” Again, “...the conventional made suspect.”

I don’t want to build a hierarchy around the images in my work or in my studio. An image I find in an archive or an image I generate by taking a screenshot of a video on YouTube can and should have the same space as one meticulously constructed and shot by me; both I view as being “mine” as much as they could be “anyone’s.” Using found and/or gathered images is part of the engagement with a kind of surreptitious image. These images relate to a kind of “operational image” or “technical image”, in that they do not portray a process in as much as they are a part of a process. I don’t believe in iconicity anymore, or that an image now could become “iconic” in the sense that we have come to understand it.

My images are meant to prod at the flops of the icon. This extends not only to the images themselves, but also to objects I engage with, whether as props to be used in service of an image, or objects that become a piece in and of themselves. What kinds of angles, vantage points, decisions in lighting or cropping show the hand of the photographer? Who do we rely on as witness to making? What kinds of marks of authenticity or visual imprimaturs do we listen to and what do we ignore? In often blurring the lines of an image’s origin and by alluding to aesthetics of various commercial or professionally-specific photographic techniques in my own shooting, I am interested in fostering a kind of anti-formalism that refutes any assumed style. Similarly, sculptural objects move between a feeling of intention and rashness, again questioning style and form.

Building my own archive (or, maybe more accurately, what Allan Sekula called a “territory of images”) is an attempt to create my own associative economy. Perhaps these exercises are a kind of portraiture. I rely on images in part to “get by”, as a way to reorient towards our habits of recognition, which includes the ways in which I extend that to myself. The work reaches outside of itself to the built world, the imaged world, and the world of commodities.

• Talking about Jenny Holzer’s “truisms”, Mike Kelley said: “.... the more you looked at it, the more you came to realize that it was your emotions and your beliefs coloring how you understood those things. And it was up to you to examine your own internalized belief systems in order to look at another system of belief.”

• Writing about Joan Didion, Hilson Als observes how, “...writing, for [Didion], can be a means of controlling the uncontrollable, including grief and loss.”

• Steven Parrino on Cady Noland: “Cady Noland’s subjects are not social anthropology but clues to herself.”

• Glenn O’Brien on Richard Prince: “...a portrait of the artist in negative space.”

I agree with all of the above and will admit to the presence of it in my work and process.

Megan Plunkett (b. Los Angeles, 1985) is an artist living in Los Angeles. She has exhibited her work in numerous solo and group shows in New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Dallas, London, and Australia. Along with Dan Wagner she has run the inimitable Kingsboro Press since 2007, a publishing project that has released such projects as The Wainwright Naked Hippie Tarot (2019) and the reprinting of Cookie Mueller and Glen O’Brien’s 1984 play DRUGS (co published with For the Common Good, 2016). Plunkett is currently studying forensic photography at the University of California, Riverside, CA.

Works in exhibition:

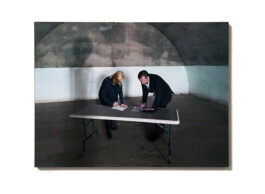

Return to Sender 01

2020

Digital print on glossy paper mounted to gatorboard

24 x 16 inches

Ed. 2 + 1 AP

Return to Sender 02

2020

Digital print on glossy paper mounted to gatorboard

9.8125 x 7.5 inches

Ed. 2 + 1 AP

F

4225 Gibson Street

Houston TX 77007

For more information, please contact Adam Marnie at office@fmagazine.info